Mavericks, California

Mavericks | |

|---|---|

4-frame image that shows the famous break of Mavericks | |

| Coordinates: 37°29′29″N 122°30′30″W / 37.49149°N 122.508338°W | |

| Location | Pillar Point Harbor, California |

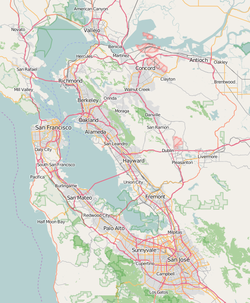

Mavericks is a surfing location in northern California outside Pillar Point Harbor, just north of the town of Half Moon Bay at the village of Princeton-by-the-Sea. After a strong winter storm in the northern Pacific Ocean, waves can routinely crest at over 25 ft (8 m) and top out at over 60 ft (18 m). The break is caused by an unusually shaped underwater rock formation.

Mavericks is a winter destination for some of the world's best big wave surfers.[1] From 1999 to 2016, an invitation-only contest called the Titans of Mavericks was held there during most winter surfing seasons, whenever the winter wave conditions there were deemed to be suitable to meet the needs of the contest.

Origin of the name

[edit]

In early March 1967, Alex Matienzo, Jim Thompson, and Dick Notmeyer surfed the distant waves of Pillar Point. With them was Matienzo's roommate's white-haired German Shepherd, Maverick, who was accustomed to swimming with his owner and Matienzo while they were surfing. The three surfers left Maverick on shore, but he swam out to them. Finding the conditions unsafe for the dog, Matienzo tied him up before rejoining the others. The riders had limited success that day as they surfed overhead peaks about 1⁄4 mi (400 m) from shore, just along the rocks that are visible from shore; they deemed the bigger outside waves too dangerous. The surfers named the location after Maverick, who seemed to have gotten the most pleasure from the experience.[2]

Description

[edit]

Sea floor

[edit]Sea-floor maps released by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 2007[3] revealed the mechanisms behind Mavericks' waves. A long, sloping ramp leads to the surface. The ramp slows the propagation of the wave over it. The wave over the deep troughs on each side of the ramp continues at full speed forming two angles in the wavefront centered over the boundaries between the ramp and the troughs. The result of this is a U-shaped or V-shaped wavefront on the ramp that contains the wave energy from the full width of the ramp. This U-shaped or V-shaped wave then collapses into a small area at the top center of the ramp with tremendous force.[4]

Left Hander

[edit]The left at Mavericks is rarely ridden, as the wave tends to be unreliable. It can be a much faster ride than the right, shooting riders down a quicker pipe barrel. Surfline says the left is "a short-lived explosion of hell and spitfire."[5]

History

[edit]

Jeff Clark grew up in Half Moon Bay, watching Mavericks from Half Moon Bay High School and Pillar Point. At that time the location was thought too dangerous to surf. He conceived the possibility of riding Hawaii-sized waves in Northern California. In 1975 at age 17 and with the waves topping out at 20–24 ft (6–7.5 m), Clark paddled out alone to face the break. He caught multiple left-breaking waves, thereby becoming the first documented person to tackle Mavericks head-on.

Other than a few of Clark's friends who had paddled out and had seen Mavericks for themselves, no big wave surfers believed in its existence. Popular opinion held that there simply were no large waves in California.[6]

Dave Schmidt (brother of big wave legend Richard Schmidt) and Tom Powers, both from Santa Cruz, were two of the next people to surf at Mavericks, surfing with Clark on January 22, 1990. John Raymond, from Pacifica, Johathan Galili, from Tel Aviv, Israel, and Mark Renneker, from San Francisco, surfed Mavericks a few days later.

Popularization

[edit]In 1990, a photo of Mavericks taken by Clark's friend Steve Tadin was published in Surfer magazine, generating interest in Mavericks. More photos of Mavericks appeared in surfing magazines, and before long, filmmaker Gary Medeiros released a movie, Waves of Adventure in the Red Triangle. As news of Mavericks spread, many big-wave surfers came and surfed there.

Death of Mark Foo

[edit]On December 23, 1994, during a week of huge swells, notable Hawaiian big-wave riders Mark Foo, Ken Bradshaw, Brock Little, Mike Parsons, and Evan Slater visited Mavericks. In the late morning, Foo rode on a late takeoff into an 18 ft (5.5 m) wave, caught the edge of his surfboard on the surface, and fell forward into a wipe out near the bottom of the wave. A few hours later, a fellow surfer traveling back to shore on a boat noticed a body in the water, which was identified as Foo. The only visible injury was a small cut on the forehead. Many surfers believe that the fall knocked the wind out of Foo and he was tied down by his leash to a rock formation.[citation needed]

The accident afforded Mavericks greater notoriety and prompted the formation of the Mavericks Water Patrol by Frank Quirarte and Clark.[6] The accident also triggered a continuing discourse around the safe use of surfboard leashes while surfing extreme waves. Many believed that Foo's surfboard leash may have contributed to his death.[7] Leash proponents defend it as a useful convenience and as insurance against losing the surfboard, a form of flotation device, a means for a fallen surfer to find the surface by following the leash cord to the buoyant board. Opponents argue that a leash can cause the rider to collide with their board in a wipe out and that the leash can also loop around the surfer's arms, legs or the neck when underwater. Quick-release velcro leashes have since become standard surfing equipment to address some of these risks.[6]

Death of Sion Milosky

[edit]Sion Milosky, an accomplished big-wave surfer, died at Mavericks on March 16, 2011. Milosky, 35, of Kalaheo, Kauai, Hawaii, apparently drowned after enduring a two-wave hold down around 6:30 PM. Twenty minutes after the incident, Nathan Fletcher found Milosky's body floating at the Pillar Point Harbor mouth.

Milosky had been named the North Shore Underground Surfer of the Year in February 2011. He used some of his $25,000 prize[8] to travel to Half Moon Bay to catch one of the last big swells of the season at Mavericks.

Women at Mavericks

[edit]In 1999, Sarah Gerhardt became the first woman to surf Mavericks.[9] In 2018, after a long fight, women were first included in the formal Titans of Mavericks surf competition, also receiving equal prize money.[10]

World Records

[edit]In 2001, Carlos Burle won the Billabong XXL Big Wave Award by riding a 68 foot (20.7 m) tall wave at Mavericks.[11]

On 23 December 2024, Alessandro "Alo" Slebir rode an estimated 108 foot (32.9 m) tall wave at Mavericks, which would exceed the current world record by over 20 feet.[12] The wave height was estimated by the Mavericks Rescue Team[13], but has not yet been confirmed by Guinness World Records.

Invitational Surfing Contest

[edit]

The first surfing contest at Mavericks was held in 1999, as the Mavericks Invitational. The competition later came to be known as the Titans of Mavericks invitational. Organizers would invite a number big wave surfers annually to compete in the one-day event, but it was only held if wave conditions were favorable during the competition season (which season ran from November 1-March 31). In 2019, after two years of cancelled competitions, the World Surf League announced that the contest had been canceled indefinitely, citing "various logistical challenges" and "the inability to run the event the last two seasons."[14] The competition has not been held since.

The Mavericks Awards is, as of 2022 a new video performance contest where big wave surfers and videographers submit their best surf content of Mavericks each season. There are 3 categories for men and 3 categories for women include Biggest Wave, Ride of the Year, and Performer of the Year.

In media

[edit]

The first videos were shot by Eric W. Nelson in February 1990, catching Clark, Schmidt and Powers. Eric was shooting for his community access television show Powerlines Surf-Spots. This was the origin of the Powerlines Productions company that showcases big wave surfing around the world.

Nelson's first film was High Noon at Low Tide 1994/1995. In 1998, he produced another big wave documentary Twenty Feet Under. Local filmmaker Curt Myers, produced Shifting Peaks and Heavy Water 1994/1995.

On December 11, 1998, they combined their efforts and produced the mini-documentary twelveleven.

Clark and Mavericks are featured in the 1998 documentary Mavericks, a one-hour PBS film that chronicles the early years, and the 2004 film Riding Giants, which documents the history of big wave surfing. Directed by skateboarder turned documentary producer Stacy Peralta (best known for the skating documentary Dogtown and Z-Boys), Riding Giants includes interviews and commentary materials with many of the surfers mentioned in this article.

In the film Zoolander, Owen Wilson's entourage includes a big wave surfer from Mavericks.

The surfing documentary film Discovering Mavericks, executive produced by Jeff Clark and directed by Joshua Pomer, features surfers like Jeff Clark, Peter Mel, Flea, Shane Dorian, Nick Lamb, Zack Wormhoudt, Brock Little and Mike Parsons, and also honors Mark Foo and Jay Moriarty.

Chasing Mavericks, a 2012 biopic about Mavericks surfer Jay Moriarity, starred Gerard Butler as Frosty Hesson, Abigail Spencer as Brenda Hesson, Frosty's wife. Jonny Weston as Jay Moriarity, Elisabeth Shue as Christy Moriarity and Leven Rambin as Kim Moriarity. Maya Rains plays Roque Hesson, while Patrick and Asher Tesler (twins) portray Lake, son of Frosty and Brenda. Moriarty's spectacular wipeout in 1994 had landed the 16-year-old surfer in the pages of The New York Times and on the cover of Surfer magazine. On December 19, 2011, film star Butler survived a near-death accident, pounded by 3.5–5 m (12–16 ft) waves. Butler was held underwater for several waves and dragged through rocks until rescued by a safety worker on a jet ski.[15] According to eyeforfilm.co.uk, "Butler was knocked off his board by a freak wave. He was trapped underwater as two more waves went over him, and witnesses say he took the force of four or five waves to the head. He was also dragged through rocks before rescuers managed to reach him and get him to the shore. Butler was conscious when pulled from the water and spent the next sixteen hours in Stanford Medical Center."[16][17]

A memoir, Making Mavericks by Frosty Hesson with Ian Spiegelman, was released by Zola Books in October 2012. The book recounts Hesson's time as one of the first to conquer the massive break at Mavericks and his mentoring of Moriarity.

On June 10, 2013, at its Worldwide Developers Conference, Apple announced that the latest version of its Mac operating system OS X (version 10.9) would be entitled Mavericks. Apple said their new operating software generations would be named after places in California that have inspired them.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Matza, Max (December 30, 2023). "Surfers take on giant waves as storm hits California". Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Warshaw, Matt (2000). Mavericks: the story of big-wave surfing. Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2652-X.

- ^ "Mavericks maps and flythrough animation". Sanctuaries.noaa.gov. April 17, 2007. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ McKenna, Phil (April 19, 2007). "Map reveals secret of awesome Mavericks waves". NewScientist.com. Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- ^ "Beta Mavericks Travel Guide and Directory". Surfline.Com. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Riding Giants". Sony Pictures Classics. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ "Mark Foo'S Final Moments". Surfline.Com. February 21, 2001. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ Wong, Kristine (March 18, 2011). "Etches in the Sand: Sion Milosky Remembered at Mavericks – Half Moon Bay, CA Patch". Halfmoonbay.patch.com. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ "Woman in the Wild: Sarah Gerhardt". Outdoor Project. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "Equal pay or no one plays? Big-wave women draw line in the sand at Mavericks". The Mercury News. August 24, 2018. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "What Are the Largest Waves Ever Surfed?". www.wetsuitwearhouse.com. Geno Seay. February 27, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Black, Lester (December 31, 2024). "A Santa Cruz surfer rode potential world-record 108-foot-tall Mavericks wave". SFGate. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ Quirarte, Frank (December 29, 2024). "alosleiber's wave". Instagram. Retrieved January 2, 2025.

- ^ "World Surf League Ends Titans Of Mavericks Competition". CBS SF BayArea. September 2, 2019. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ "Gerard Butler's 'near death' surfing mishap". USA Today. December 20, 2011.

- ^ Jennie Kermode (December 20, 2011). "Gerard Butler hospitalised after surfing accident". Eye For Film.

- ^ Frank Quirarte (December 19, 2011). "Gerard Butler survives two-wave hold-down at Mavericks". ESPN.

- ^ "Apple announces OS X Mavericks". iDownloadBlog. June 10, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

External links

[edit]- Titans of Mavericks (Official Contest Site)

- Mavericks on Surfline

- Mavericks on BlooSee

- 25, 2009+09:37:15 Quiksilver 'The Men Who Ride Mountains' contest at Mavericks

- Mavericks Big Wave Surf Competition 2006 – Photos & Article

- Mavericks Big Wave Surf Competition 2005 – Photos & Article

- Mavericks Big Wave Surf Competition 2004 Photos by Steve Waterhouse

- Science of Big Waves, a KQED short documentary on Mavericks